Kaixo! I’ve just Hello to you in Euskera, the language spoken by the people of the Basque Country, or Euskal Herria (the country of Euskera): a territory on either side of the western Pyrenees, part of which is in Spain, and the other part in France. The origins of Euskera arouse great curiosity because it’s Europe’s oldest language, and is unrelated to any other language.

It’s so different from other languages, in fact, that all you have to do is take a look at some months of the year in Basque and in Spanish. For example, January is urtarril, February is otsail, and June is ekain. It’s a survivor language, because it all but disappeared in the 20th century after decades of bans and repression by the Spanish and French states.

Considerable research has been carried out into the origins of Euskera, but to this day we still do not know where the Basque language comes from – at the present time it is spoken by almost one million people, like me. Here you can listen to a report I did in Myanmar in 2015 during my time as correspondent for EiTB (the Basque Country’s radio and television network). See what my mother tongue sounds like to you.

Leading hypotheses on the origins of Euskera have attempted to relate it to Etruscan, Berber, and ancient non-Indo-European languages of Europe, meaning most languages on the Old Continent. According to philologist Asier Larrinaga, however, to date no links have been found between Euskera and Hungarian, Finnish, the languages of Lapland and the Baltic countries, or Caucasian languages. There’s nothing beyond the odd causal word with a similar format and meaning in both languages.

Larrinaga, head of EiTB’s Euskera service and a colleague of mine, says that the last hope of any possible relationship lies in Iberian. But since 1922, when historian Manuel Gómez Moreno made a start on deciphering writings and texts were read in Iberian (albeit without understanding them), no similarities have been found between Basque and Iberian.

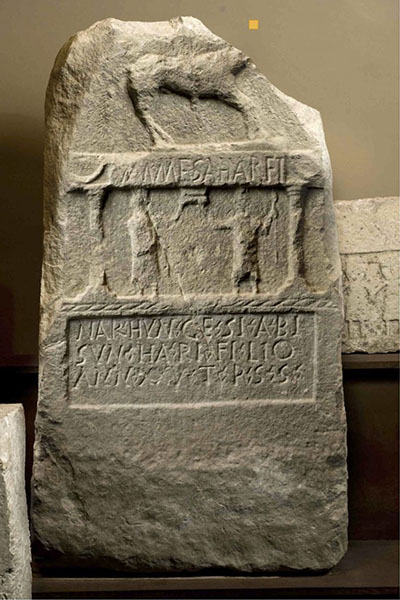

Influence of Latin. In any case, the fact that no close relationships have been found does not mean nothing is known about the trajectory of the Basque language down through the ages. What is known, through the names of people and gods on funeral stelae from the Roman era (1st – 3rd century A.D.), is that a predecessor of today’s Euskera, known as Protoeuskera, occupied a territory which largely matches the area historically occupied by Euskera.

The tombstones were written in Latin, but the people’s names were Basque: Zezengorri (Red Bull), Anderetxo (Little Woman) or Ummesahar (Old Child). The last-named may be seen in the photo below, the property of the Government of Navarra. The clearest traces have been found in Aquitaine, southwest France, and so Protoeuskera is also known as Aquitaine.

Euskera is definitely a language that has been heavily influenced by Latin, considering the long period over which they remained in contact, according to Asier Larrinaga.

It is for this reason that many Basque names originate from Latin. For example, gauza (thing), comes from causam; errege (king) comes from regem; kipula (onion) comes from caepulam; bake (peace) comes from pacem. Latin also influenced Basque phonetics and morphosyntax. The Latin suffix -tu is used to create verbs such as aditu (listen) or begiratu (look), which respectively originate from auditum (hear) and vigilatum (watch over). Later, Euskera imitated the devices used to form the future of Romance languages or languages derived from Latin, such as Spanish, Portuguese, Italian or French.

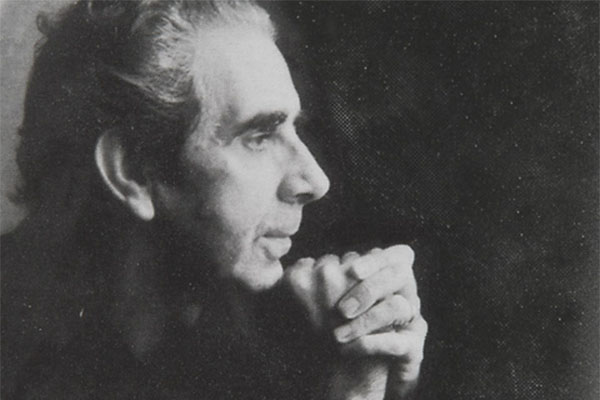

These influences arose centuries before Euskera took up its place in History. Koldo Mitxelena, the great patriarch of Basque Philology, was the first to conduct an in-depth survey of this archaic Euskera in his book on the history of Basque phonetics, Fonética histórica vasca (1961).

In his huge work, acclaimed philologist Mitxelena reconstructed the common original format of many Basque words on the basis of present dialectal variants.

In this way, for example, he concluded that the words ardao, ardo and arno, which mean ‘wine’, come from the protoform ardano. The present words for ‘cheese’, gaztai, gasna and gazta, originate from gaztana. It should be pointed out that our language may be called either Euskara or Euskera, precisely depending on the dialectal variant we refer to.

Why did Euskera fragment into dialects? According to Mitxelena, the dialects of Euskera emerged after the 6th century, thus doing away with theories attributing the origins of the different forms of speech to a number of tribes during the Roman era. Mitxelena cites changes in political and social conditions between the 5th and 6th centuries which produced an increasingly fragmented society, in turn leading to the creation of dialects within each new power centre.

Dialectal variants represent considerable linguistic richness, although they can also impair comprehension among people speaking markedly different dialects. To overcome these constraints, we have what is known as the batua form of Euskera

Euskara batua is the unified Basque language, the guidelines for which were laid down at the 1968 Congress of Euskaltzaindia, the Royal Basque Language Academy. The congress was held at the Arantzazu sanctuary, a most important location in Basque culture.

Batua Basque is the variant that has been used by the authorities, in education and in media since the 1980s. Euskera co-exists alongside Spanish in Spain and French in France. It is an official language in Spain. It has not attained any such status in France, and so its situation there is worse.

However, Euskera has made much progress in comparison to the mid-20th century, when it all but became extinct. In Spain it suffered under Franco’s dictatorship, which banned it. France has never granted linguistic rights to the speakers of any languages other than French, and simply due to pressures arising from the modern age, the State has found itself obliged to make a start on addressing its local languages. Whatever the constraints that Euskera may encounter, however, the main responsibility for its survival is shouldered by those who speak it. In the words of poet, musician and writer Joxean Artze, a language does not die out because those who do not know it do not learn it, but because those who do know it do not speak it:

❝ Hizkuntza bat ez da galtzen ez dakitenek ikasten ez dutelako,

dakitenek hitzegiten ez dutelako baizik ❞

***